My first two boys were born eighteen months apart. In my circle of friends, I was “that mom” with two under two. And while I was extremely overwhelmed in more ways than one, I was also secretly confident that I had it figured out.

I mean, born so close together, how different could they really be? I figured between a slew of Matchbox cars, Thomas trains, and a variety of moving objects (tricycles, balls and bubbles), we were good to go. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

I’m a certified practitioner of a variety of psychometric assessments (Myer-Briggs, CultureActive, and icEdge, to name a few), and I believe these are helpful tools to help us understand our inherent gifting and talents and also be mindful of areas of personal growth.

But it can be easy to forget to extend this mindfulness to our own children. It took time for me to understand, and differentiate between, the personalities of my kids.

Even as a toddler, my eldest, Shepherd, was sociable, structured—nap times were fairly rigid or it was meltdown-city—and born with an amazingly logical mind. I remember fretting that he used to make patterns out of his Magna-Tiles instead of building castles or towers.

But my husband pointed out that he was advanced in his own way—complex patterns of shapes and colors aren’t easy for a three-year-old!

He took to reading phonetically, devouring blends and the like. One day I saw him daydreaming and, given that it was December, assumed it was about something Christmas related.

When I prompted him, he answered seriously, “Mommy, I am thinking about commas and those big lines with dots at the end.” Apparently my logic-lover had discovered punctuation in preschool that morning, and it blew him away.

Meanwhile, his younger brother, Rock, who kept up with him at a ferocious pace in many ways, would wander away during playgroup. In a melee of toddlers and babies, I would startle when I couldn’t find him—only to discover him upstairs playing by himself at his train table.

Not understanding his need for solitude, I would scold him, thinking that he was being naughty and tried to hide.

Eventually, my husband and I realized that we had two very different children on our hands: a logical, structured extrovert and a dreamy, spontaneous introvert.

And we had to navigate how to parent through the disparities: Do you cater to their personalities? Shield the introvert from every overstimulation (read: four-year-old birthday parties), or force the extrovert into two hours of quiet time when they are jumping out of their skin?

As our circumstances changed, we discovered some of the answers we needed. Less than three years after my second son, my daughter was born and diagnosed with tracheomalacia, a congenital condition. Though it wasn’t severe, her pediatrician cautioned us about viruses and colds, which her weak immune system wasn’t equipped to handle.

At this point, my oldest son was starting school, and I’d planned to put my three-year-old in preschool. But my daughter’s condition led me to keep my second son home, worried he’d pick up germs he could pass to her.

My little introvert was happy as a clam to be at home, having playdates, exploring the local parks and museums as we had always done. At the time, I didn’t realize how beneficial this decision was.

The extra time with him taught me so much. I began to see how much he blossomed with time alone—he would happily “read” in his room or play trains for over an hour (an amazing contrast to my eldest who needs people with him after about 15 minutes).

He was very sociable at playgroups, but didn’t seem to crave that time the way my eldest does—to the point that I began to re-think four-year-old preschool.

I had never thought of myself as a homeschooling mom, but I began to research various curriculums. It dawned on me how wonderful this could be, how much of a gift to him in his personality development at this tender age.

Homeschooling was a sacrifice in many ways, but we had a blast, and as his sister grew older, she joined in with songs, games and stories. We chose to parent according to external circumstances (the tracheomalacia) coupled with what we discerned to be best for his personality.

He is eight years old now, and in school full-time, but we are always cognizant of giving him space after school and on weekends to recharge, which he needs more than his more extroverted siblings.

With my oldest—who, like his mama, will happily pack his schedule full to the brim—I focus on teaching the benefit of protecting “white space” in his calendar. He’s nine years old and naturally athletic, but so far we’ve avoided travel sport teams, opting to give him more unstructured time to explore the sciences and use his imagination.

My daughter, at age 4, seems to be a unique mix. Myers-Briggs cautions against typecasting before age 7 as personalities are still emerging and developing, but right now I see her as an ENFP based on comments like this: “Mama I want to be an artist, a scientist, and a teacher” (as she tries on her fifth outfit for the day).

Life is for sure not always catered to our needs; sibling strife is unavoidable as are parental disputes. But I find that this all leads back to a mindfulness mentality—the need to be mindful of how our children are naturally wired.

We had to pay attention to discover how to parent our children effectively, to realize that while my eldest ESTJ son thrives under clear and direct correction, my INFP son needs more gentle discipline, as he will internalize everything negatively.

And my own childhood experiences were sometimes stumbling blocks. I am Latina, and correction in my culture is very authoritarian in style. Initially—and without even realizing it—I used this same method with my firstborn, who responded well it since it was no-nonsense, clear and direct.

That gave me a sense of misplaced confidence with my second son—until it didn’t work at all for him. Around age four, we noticed that he had a pattern of negative self-talk that would emerge after we had corrected him.

Our own childhood experiences are sometimes stumbling blocks.

We began to realize this more sensitive nature of his required a more creative discipline style, one that involved less authoritarian tone of voice and concrete time-outs and more eye contact, lower gentler tone and more physical touch (hands lightly resting on his hand or knee while we discussed what we were correcting, and why).

While that doesn’t come naturally to my husband nor me, we’ve had to be mindful about changing our approach to make sure that our correction comes through and doesn’t need to be filtered through all his emotions.

All this to say that you do not need a psychometric assessment to know your child well (though it doesn’t hurt!). Lots of time (we are talking quantity, not just quality) will allow you to clearly see their natural personalities emerge.

And sometimes you need to adjust our parenting to allow those personalities to develop healthily. After all, affirming your children in their natural abilities, and gently working on their growth areas, is one of the biggest gifts a parent can provide.

Natalie d'Aubermont Thompson

Related posts

Recent Posts

Flooring Renovation: Asbestos Removal and Choosing the Perfect Floor Stain

We finally completed the renovation of our first-floor flooring, and like most renovations, it was a bit more involved than we initially hoped for. When we bought the house three years ago, we knew the…

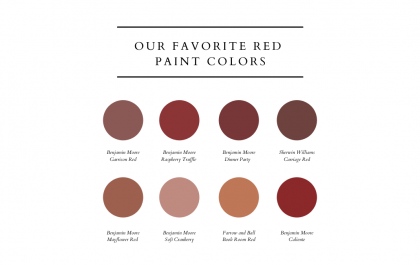

Roses are red: 8 beautiful shades of a paint color you might not realize you love

Lots of us love blues, greens, whites, and greys. And if neutrals are more your thing, you might think you need to stay far away from a color like red. But we think it’s worth…